So, you’re about to tackle a literature review. It’s a task that can feel a bit daunting, but it’s really about stepping into an ongoing academic conversation. Your job isn’t just to repeat what others have said; it’s to critically analyse the existing research, spot the gaps, and figure out where your own work fits in. Getting this right comes down to having a sharp focus, a logical structure, and a clear method for piecing it all together.

Defining Your Focus for an Effective Review

Starting a literature review can feel like standing at the bottom of a mountain, surrounded by a dizzying number of books and articles. The secret isn't to read everything in sight. Instead, it’s about knowing exactly what you're looking for before you even begin. A well-defined focus is your map—it’ll guide you through the academic terrain and keep you from getting lost.

Think of yourself less as a student writing a book report and more like a detective on a case. You're gathering clues (research findings), interviewing witnesses (the authors), and building a narrative that reveals what’s known, what’s still debated, and what remains a complete mystery. This first stage is all about narrowing down a massive subject into a sharp, manageable research question.

From Broad Topic to Focused Question

The most common trap students fall into is starting with a topic that’s far too broad. Let's say you pick "mental health in the UK." You could write an entire library on that! To write a successful review, you need a laser focus.

To get there, start asking yourself some targeted questions:

- Who? Which specific group are you interested in? Think university students, new mothers, or retired men.

- What? Which specific part of mental health are you exploring? Maybe it’s anxiety, the influence of social media, or access to support services.

- Where? Is there a particular setting? This could be urban areas, online communities, or rural locations.

- When? Are you looking at a specific timeframe, like the post-pandemic period or the last decade?

Using this method, "mental health in the UK" quickly becomes something much more focused, like: "How has the use of social media platforms affected anxiety levels among UK university students since 2020?" Suddenly, you have a question that’s specific, measurable, and gives your research clear boundaries.

This skill is absolutely vital for adult learners. For students on an Access to Higher Education Diploma, mastering the literature review is crucial because it builds the critical thinking abilities you’ll need to thrive at university. While undergraduate continuation rates were 89.5% in 2021-22, mature learners can sometimes face more challenges with academic tasks like this. You can learn more from the statistics on the Office for Students website.

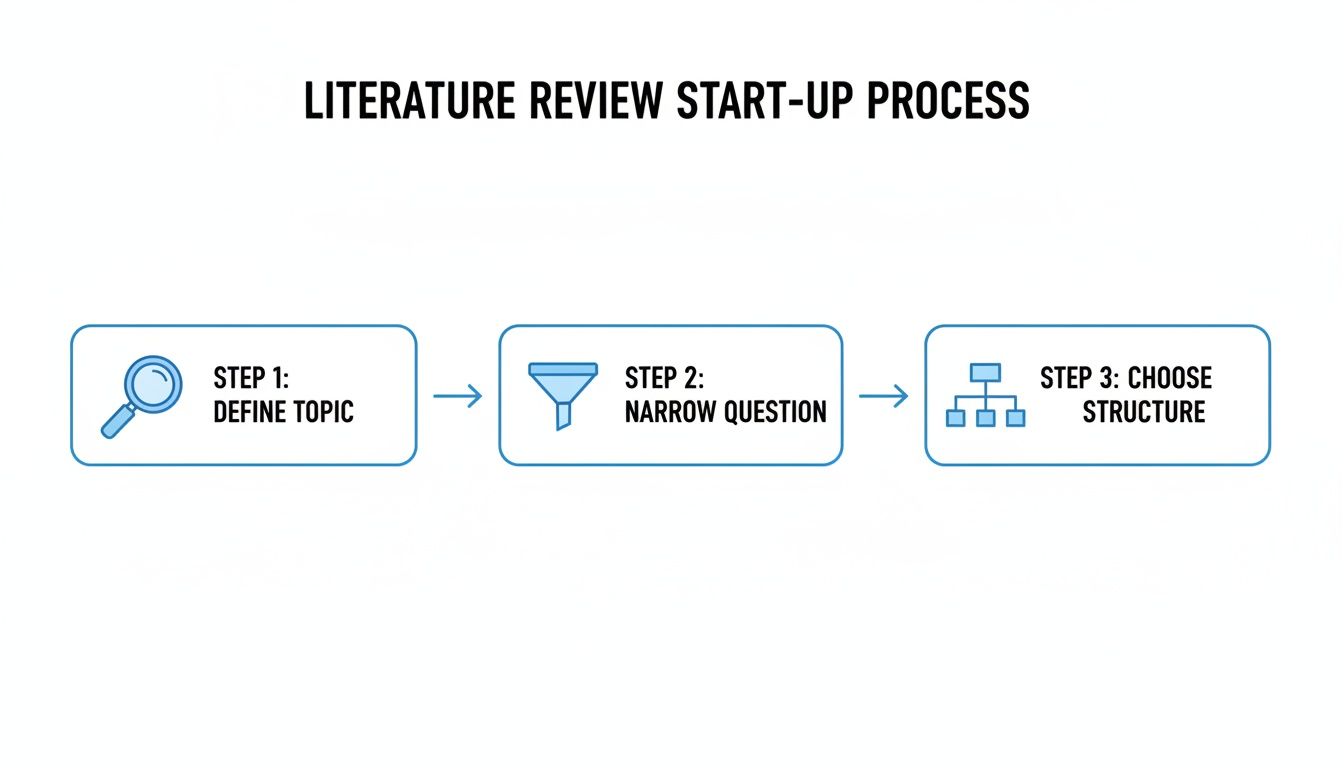

This simple flowchart shows how to refine your focus and get started.

As you can see, moving from a general topic to a specific question and then choosing a structure creates a clear path forward.

Choosing Your Literature Review Structure

Once your question is locked in, you need a plan for organising your findings. The structure you pick will depend entirely on your research goals and the story you want to tell with the evidence you’ve gathered.

A literature review's structure is its backbone. It provides the support needed to hold your arguments together and present them in a logical, compelling way. Without a clear structure, even the best research can feel disjointed and confusing.

There are three main ways to structure your review. Deciding which one to use is a key step in the planning process.

Choosing Your Literature Review Structure

This table breaks down the three most common structures to help you decide which approach is the best fit for your research question and topic.

| Structure Type | Best For | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Thematic | Exploring recurring concepts, debates, or ideas across different studies. | Organised by common themes, allowing you to compare and contrast various authors' viewpoints on a single topic. |

| Chronological | Showing the historical development of a topic over time. | Traces how research and understanding have evolved, highlighting key shifts and turning points. |

| Methodological | Analysing how different research methods have been used to study a topic. | Groups sources by their methodology (e.g., qualitative vs. quantitative), ideal for when the how is as important as the what. |

Most students, especially at the Access Course level, find that a thematic structure is the most effective. It allows you to build a strong, argument-led review that demonstrates your ability to synthesise information rather than just describe it. However, the best choice always comes back to your specific research question.

Finding and Managing Your Academic Sources

Right, you’ve got your research question pinned down. Now it’s time to start gathering your evidence. This part is all about finding top-quality academic sources without getting lost in a sea of search results. It’s a real skill, blending smart searching with disciplined organisation right from the get-go.

Think of it like stocking your kitchen before cooking a big meal. You need specific, high-quality ingredients (like peer-reviewed articles and academic books), and you need to know exactly where you’ve put everything. Let’s start with where to find them.

Mastering Your Search Strategy

Your usual search engine is fine for day-to-day questions, but for a literature review, you need to head to academic databases. These are basically curated libraries of scholarly work. Your local or university library will likely give you access, but some great ones are freely available.

Here are a few key places to start your hunt:

- Google Scholar: A fantastic, free starting point that indexes scholarly literature across loads of different subjects.

- JSTOR: A digital library packed with academic journals, books, and primary sources. Many universities provide access to this.

- EThOS (from the British Library): A goldmine for finding UK doctoral theses, which often contain incredibly detailed literature reviews on niche topics.

To get the best out of these databases, you need to speak their language. That means using Boolean operators—simple words that make your search much more precise.

- AND narrows things down (e.g., "social media" AND "student anxiety").

- OR broadens your search (e.g., "university" OR "higher education").

- NOT gets rid of things you don't want (e.g., "mental health" NOT "children").

Using these will help you pinpoint the most relevant articles and save you hours of sifting through stuff that isn't useful.

Staying Organised from Day One

Finding your sources is only half the battle; keeping them organised is just as crucial. A messy folder system is the enemy of a good literature review. We’ve all been there – you find a brilliant article, only to completely lose track of it a week later.

The single best piece of advice I can give is to start an annotated bibliography from the moment you begin searching. It feels like extra work at first, but it will save you an incredible amount of time and stress later on.

An annotated bibliography is just a list of your sources where you write a short paragraph for each one. You summarise its main argument, point out its strengths and weaknesses, and jot down how it relates to your research question. This forces you to think critically about every source as you find it.

You can manage this process using a few different tools:

- Reference Management Software: Tools like Zotero or Mendeley are brilliant for this. They help you save, organise, and cite your sources automatically.

- A Simple Spreadsheet: A spreadsheet with columns for the author, year, title, key findings, and your own notes is a low-tech but really effective alternative.

Whichever method you pick, the important thing is to make it a habit. By summarising and critiquing as you go, you’re basically writing your literature review in small, manageable pieces. This also helps build better note-taking habits; you can find more tips in our guide on how to take effective notes.

For those using multimedia sources like lectures or conference talks on YouTube, look into converting YouTube content into text for academic purposes. It can make analysis and note-taking so much easier.

When you finally sit down to write the full draft, you won’t be staring at a blank page. Instead, you'll have a rich collection of organised notes and critical thoughts, all ready to be woven together.

Connecting Ideas and Building Your Argument

So, you've gathered your sources and made your notes. Now for the most important part: turning all those individual summaries into a single, compelling argument. This is where you shift from being a collector of information to a critical thinker. A great literature review doesn't just list what others have said; it weaves their ideas together to tell a story about the current state of knowledge on your topic.

This process is called synthesis. It’s about spotting the connections, contradictions, and conversations happening between different authors. Getting this right is what elevates your work from a simple summary to a piece of genuine academic scholarship, showing you’re ready for university-level study. It’s how you find your own voice and prove to your tutor that you don’t just understand the material—you can really engage with it.

From Reading to Synthesising

The first real step in synthesis is to look for patterns across your sources. Instead of thinking about each article on its own, start grouping them together. You’re looking to identify the main themes, ongoing debates, and crucial gaps that emerge when you look at all the research as a whole.

As you go through your notes, start asking yourself a few key questions:

- Which authors agree on a key point? Grouping studies with similar conclusions can form the foundation of a paragraph or even a whole section.

- Where are the major disagreements? Highlighting conflicting findings or different theoretical approaches is a brilliant way to demonstrate critical analysis.

- Are there concepts that pop up again and again? These recurring ideas are your main themes and should give you the structure for the body of your review.

- What is consistently missing? Pinpointing what isn't being discussed is how you find the research gap your own work might eventually fill.

This process requires a sharp, analytical mind. If you feel like you could use a bit of a boost in this area, our guide on how to develop critical thinking skills has some practical exercises and techniques that will be a massive help here.

Practical Tools for Connecting Sources

Trying to see the connections between sources can feel a bit abstract. Making it visual can really help. When you can map ideas out, either on paper or on a screen, they become much clearer. Two of the most effective ways to do this are synthesis matrices and mind maps.

A synthesis matrix is basically just a table or spreadsheet. Down the first column, you list your sources. Across the top row, you list the key themes you've identified. Then, in the boxes, you briefly summarise what each author says about each theme.

Here’s a simple example for a review on student anxiety and social media:

| Source | Definition of Social Media | Impact on Sleep | Link to Academic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smith (2021) | Focuses on image-based platforms like Instagram. | Finds a strong negative correlation. | Suggests indirect impact via poor sleep. |

| Jones (2022) | Includes forums and messaging apps. | Notes a weaker link than Smith. | Finds no significant direct correlation. |

| Khan (2023) | Argues for a nuanced, platform-specific definition. | Agrees with Smith but for different reasons. | Argues it impacts social integration more. |

This simple grid instantly shows you where authors agree (the impact on sleep) and where the big debates are (the definition and the link to academic performance). These become the talking points for your review.

A mind map, on the other hand, is a much more free-form way to link ideas. Pop your central research question in the middle. Create main branches for your key themes, and then add smaller branches for individual authors, jotting down their specific arguments. Use colours and lines to connect related or conflicting points across different themes.

Developing Your Academic Voice

As you start grouping sources and mapping out their connections, your own academic voice will begin to emerge. Synthesis isn't just about reporting what others have found; it's about interpreting those findings and building a narrative around them. Think of yourself as the guide leading the reader through this scholarly conversation.

Use transitional phrases to show how ideas relate to one another. For instance:

- To show agreement: "Similarly, Jones (2022) builds on this idea by..."

- To show contrast: "However, Khan's (2023) findings present a challenge to this view..."

- To highlight a gap: "While much of the research focuses on sleep, few studies have explored..."

By consciously connecting, comparing, and critiquing the literature, you position your own work within the wider academic landscape. You show that you’ve done more than just read—you've understood the bigger picture and are ready to add to it. And that, really, is the ultimate goal of any literature review.

Structuring and Writing Your Draft

You’ve done the heavy lifting of synthesising your sources, turning a pile of articles into a web of connected ideas. Now, it’s time to give those ideas a home. Drafting is all about translating your mind maps and notes into a clear, compelling story that walks your reader through the academic conversation you've been exploring.

Think of yourself as an architect. You have all your materials ready—your research, your critical notes, your themes. The next job is to create a blueprint. For a literature review, that blueprint has three essential parts: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. Each has a specific job to do in making your argument stick.

Crafting a Compelling Introduction

Your introduction is the front door to your review. Its mission is to grab the reader, set the scene, and provide a clear map of the journey ahead. It needs to be punchy and powerful, setting the tone without giving everything away. A great introduction doesn't just announce your topic; it argues why this review even needs to exist.

Start broad to get your reader settled, then quickly zoom in on your specific research question. This shows you have a sharp focus. Finally, you need to signpost the structure, giving a brief preview of the key themes you’ll be unpacking in the body.

Your introduction makes a promise to the reader. It promises to tackle a specific problem, navigate a field of research, and land on a meaningful insight. The rest of your review is you keeping that promise.

Building the Body Around Your Themes

The body is where your synthesis truly comes to life. This section should absolutely not be a list of summaries—"Author A said this, then Author B said that." Instead, organise it thematically. Each paragraph, or group of paragraphs, should be dedicated to a single concept, debate, or idea you pulled out during your synthesis phase.

Kick off each paragraph with a strong topic sentence. This acts like a signpost, telling the reader exactly what that paragraph will cover. For example, instead of “Smith (2021) found that…”, try something like, “A major debate within the literature centres on the impact of social media on adolescent sleep patterns.” This immediately puts the theme, not a single author, in the spotlight.

From there, it's all about bringing different authors into conversation with one another.

- Show agreement: "Similarly, Jones (2022) provides further evidence for this, suggesting that..."

- Highlight disagreement: "In contrast, Khan's (2023) research offers a competing perspective, arguing that..."

- Critique a source: "While Smith's (2021) study is influential, its reliance on self-reported data is a notable limitation."

Using these kinds of phrases is what creates that smooth, analytical flow and proves you’re engaging critically with your sources.

To help you keep track, here's a quick rundown of what each section of your literature review needs to accomplish.

Essential Components of a Literature Review

| Section | Purpose | What to Include |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | To set the context, state the review's purpose, and outline its structure. | Background on the topic, statement of the research question/focus, and an overview of the key themes to be discussed. |

| Body Paragraphs | To critically analyse and synthesise the existing literature around specific themes. | Thematic organisation, comparison and contrast of different authors' views, and evaluation of source credibility. |

| Conclusion | To summarise the key findings, state the review's contribution, and identify gaps. | A brief recap of main points, the overall significance of the literature, and a clear statement of the research gap. |

This table is a great checklist to have by your side as you write, ensuring you don't miss any crucial elements.

Writing a Powerful Conclusion

Your conclusion is your final chance to make an impact. It should do much more than just rehash what you’ve already said. A strong conclusion summarises the big picture, underlines the importance of the literature, and—most importantly—points to what’s next.

A great conclusion should do three things:

- Summarise the key findings: Briefly pull together the main themes, points of agreement, and ongoing debates. What's the current state of play in this field?

- State the contribution of the review: What new understanding has your synthesis brought to the table? What are the big takeaways?

- Identify the research gap: This is the mic-drop moment. Based on everything you've reviewed, what’s still missing? Where are the unanswered questions? This is where you explicitly point out the gap your own research is going to fill.

Ending on the research gap is a classic power move. It proves your literature review isn't just a backwards-looking summary but a vital piece of scholarship that sets the stage for new work. It frames your own project as the next logical step in the academic conversation.

Mastering this skill is what separates good students from great researchers. According to UKRI's 2023 analysis, there were 114,405 postgraduate researchers in 2020/21, making up a select 4% of the UK's higher education population. To get to that level—where benchmarks like REF 2021 rated 48% of English Studies research as 'world-leading'—requires exactly these kinds of exceptional synthesis skills. You can read more in the UKRI's literature review on postgraduate research.

Revising and Polishing Your Final Review

Getting that first draft down is a massive achievement, but the real magic happens in the editing. This is where you transform a good piece of writing into a great one, polishing your hard work until it shines. It’s all about taking a step back, looking at your review with fresh eyes, and refining everything from the overarching argument down to the tiniest comma.

Think of it like being a sculptor. Your first draft is the big, rough block of stone—the basic shape and substance are there. Now, it’s time to chisel out the fine details, smooth the edges, and make your creation come alive. This isn’t just about catching typos; it’s about sharpening your ideas until they’re crystal clear and compelling.

A Practical Checklist for Revision

Revision is all about the big picture. Before you even think about grammar, you need to be sure your argument holds water and your structure is solid. It's surprisingly easy to get lost in your own writing, so having a checklist can be a game-changer.

Run through these questions one by one:

- Does my introduction clearly set the scene? Your reader needs to know exactly what to expect from the very first paragraph.

- Is my argument consistent from start to finish? Make sure your main points connect logically and you haven't accidentally contradicted yourself.

- Does each paragraph focus on a single theme? Check that your topic sentences are strong and that you’re not trying to cram too many ideas into one space.

- Is every single claim backed up by evidence from the literature? This is non-negotiable in academic writing. Double-check that you haven’t made any assertions without support.

- Have I gone beyond just summarising? Look for places to strengthen the connections between sources, highlighting where they agree, disagree, or where the gaps in research are.

The goal of revision is clarity. Ask yourself, "If I knew nothing about this topic, would this review make perfect sense to me?" If the answer is no, you still have some refining to do.

Simple but Effective Proofreading Techniques

Once you’re happy with the overall structure and flow, it’s time to zoom in on the sentence level. Proofreading is the final polish that makes your work look professional and read smoothly. Our brains are clever and often auto-correct mistakes as we read our own writing, so you need a few tricks up your sleeve.

A fantastic tip is to read your work out loud. It forces you to slow down and helps you catch awkward phrasing, clunky sentences, and typos your eyes might have skimmed over. You’ll be amazed at what you hear.

Another powerful technique is to temporarily change the font or background colour of your document. This simple switch tricks your brain into seeing the text as something new, making it much easier to spot errors you’ve become blind to.

Finally, don't underestimate the power of digital tools. Software like Grammarly can be a lifesaver for catching grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and punctuation issues. It's not a substitute for your own careful proofreading, but it's an excellent safety net.

Getting and Using Feedback

Getting a second pair of eyes on your work is one of the most valuable things you can do. Your Access Courses Online tutor is an incredible resource—they are there to guide you! Don't hesitate to share a draft with them and ask for specific feedback on your argument or structure.

When you get feedback, try to approach it with an open mind. It isn’t a criticism of you; it’s a constructive tool to help you improve. Focus on understanding the core suggestions and turning them into real improvements in your review. A fresh perspective can often highlight issues you were simply too close to see.

Lastly, make sure your referencing is flawless. Inconsistent or incorrect referencing can easily cost you marks. If you need a refresher on the specifics, our guide on how to reference a journal article using the Harvard style is an excellent resource to check before you submit. This final polish ensures your review meets university standards and is ready to impress.

Common Questions About Literature Reviews

Even with a perfect plan, it's completely normal for questions to pop up when you're getting to grips with writing a literature review. It’s a complex piece of work, and figuring out the finer details is all part of the learning curve.

Let's walk through some of the most common queries we hear from students on our Access to HE Diploma courses. Getting these right can make a world of difference to your final grade and your confidence as an academic writer.

How Many Sources Do I Need for a Literature Review?

This is the big one, and the honest answer is always: it depends. There’s no magic number that fits every assignment. The very first thing you should do is check your assignment brief, as it will often give you a specific range to aim for.

If it doesn't, here’s a general rule of thumb:

- For an Access to HE Diploma assignment, you might look to use 10-15 high-quality sources.

- When you get to an undergraduate dissertation, this could jump to 30-50 sources or even more.

The most important thing to remember here is quality over quantity. It’s much, much better to properly read and understand 15 highly relevant, peer-reviewed articles than to just skim through 40 and list them. Your focus should be on finding the key, foundational studies in your field as well as credible, up-to-date research.

What Is the Difference Between a Literature Review and an Annotated Bibliography?

It’s so easy to get these two mixed up, but they serve very different purposes.

Think of an annotated bibliography as a simple list of your sources. For each one, you write a short paragraph—the annotation—that summarises and gives a quick evaluation of that single source. It’s basically a series of separate, standalone mini-reviews.

A literature review, however, is a single, flowing piece of writing. It does much more than just list sources; it synthesises them. You’re weaving information from multiple authors together to build a cohesive argument, often grouping studies by theme to highlight the debates, connections, and relationships between them.

An annotated bibliography is like a collection of individual bricks. A literature review uses those bricks to build a structured wall, showing how each one fits with the others to create a bigger picture.

How Do I Find the Gap in the Literature?

Finding a "gap" in the research sounds like a huge, intimidating task. But really, it just means spotting an area that other academics haven't fully explored yet. This is the sweet spot where your own research can add something new and valuable to the conversation.

The trick is to read your sources with a critical eye. As you go, keep asking yourself questions:

- What are the limitations of this particular study? Did they only look at a small group of people?

- What questions do the authors admit are still unanswered?

- Where do different researchers seem to disagree with each other? That's often a clue!

- What do the authors themselves suggest for future research in their conclusion? They often point you right to the gaps.

Often, a gap isn't some massive undiscovered theory. It can be as simple as applying an existing idea to a new group of people or a different context, or maybe addressing a weakness you've noticed in how previous studies were conducted.

For students wanting to dive even deeper, there are plenty of excellent resources out there. If you're looking for another perspective or more detailed steps, an in-depth guide to writing a literature review could be a really valuable read.

At Access Courses Online, we provide dedicated tutor support to help you master skills like these, ensuring you're fully prepared for university. Find out more about our accredited online Access to HE Diplomas.